Into the Woods - A Pomo Scrum Beneath the Trees

Over the weekend I made one of my rare visits to the cinema. Sightings of Sasquatch, a chupacabra riding a bicycle, or Nessie doing the backstroke at Loch Ness are as likely as sightings of me at the movies. Why? It costs too much, people eat pop corn like horses feeding from a trough, and the whole thing takes too long. Our most recent selection, Into the Woods, sported each of these dreaded elements of the cinema; a $50 family price tag, a family of stallions with a barrel of endless pop corn seated just behind us, and a 2+ hour runtime. Apparently we have lost the art of telling a story in less than half a day.

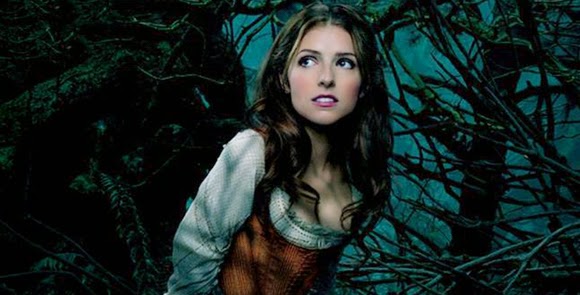

My synopsis of Into the Woods: your favorite childhood fairy tales in a rugby scrum beneath the trees. My wife called it Les Miserables Disney style as nearly all of the dialogue of the seemingly never to end movie is sung. I imagine it will be one of those movies that I don’t particularly enjoy while everyone else on the row may be giddy as girls about it. In fact, my youngest said it was her favorite movie. Congratulations Into the Woods, you have unseated Night at the Museum 3 which held her top movie spot for a whopping four days. Enjoy it while you may, given her track record you will be unseated on her next romp to Regal. When it comes to movies, she loves ‘em and leaves ‘em.

I will spare you the synopsis and the details of a critical review. I am not a movie critic by trade and PluggedIn.com is more than adequate to offer the christian version of At the Movies. I am a preacher and so it should come as no surprise that I view movies as messages. Movies are culture sermons. As such, Into the Woods has a lot to say to us.

The film is the latest installment of what seems like a lingering decade of revising our favorite fairytales. Some of it has been done in jest, taking our familiar heroes and villains and recasting them in new worlds and situations. For me, Shrek was best at this. Like Shrek, many films have come along to poke fun at the genre of the fairytale all together. I love the satire when the magical, all is good life meets the real world. The princess has been most often the butt of the joke. Amy Adams in Enchanted was a prime example.

But then we have a long list of compelling revisionary tales that have been popping up on stage, television, and on the big screen such as Wicked, Mirror Mirror, Maleficent, and Grimm. Into the Woods is the latest edition that seems to be carrying forward the conversation with our culture; asking an important question. Who is responsible for evil and how do we solve it?

There is a side of me that enjoys these reimagined tales. From a purely storyteller perspective I give the writers kudos. I am not one who would chide our culture’s storytellers as being uncreative; attributing this rash of revisionism to a lack of originality. In fact, I would think as a storyteller that these revisions are somewhat courageous. Who else would dare to take these iconic tales and dare to tamper with them? In some ways it is like an artist adding paint to Mona Lisa. You would have to be an idiot with a brush to try such a thing. But these storytellers have pulled it off. Why? Because our culture has given them permission to rethink the stories. Postmodernism has been an amusement park of revisionism in every field from history to morality to math. We don’t even solve problems like we once did.

Yet permission for revision doesn’t just come as a style choice of this young century. Revisionism is a necessity in a culture that has flushed away absolutes and intentionally blurred the lines. Postmoderns want to think all they do is good. Tolerance is a false utopia and in a strange way, our new fairytale.

All is well in our tolerant, fairytale garden utopia until we have a clash with the real world - where there is such a thing as evil whether we want to believe in it or not. Everyone is fine in the scrum in the woods, the homosexual, the atheist, the hedonist, the pluralist, and the rest of us until a giant comes stomping through the trees. A madman guns us down in the theater. A terrorist kidnaps and kills girls in a school. Isis beheads a journalist. It is here that the crisis of relativistic culture begins. Instead of asking what is evil, we are forced rather to ask, who’s to blame?

Like the rest of the revisionist fairytale films, Into the Woods casts both hero and villain in new light. It is ironic that these films begin to explore the flaw of relative morality - as much as we want it to be so, all we do is not good. Evil exists and it is coming to destroy us.

The revisionist fairytale films are redemptive in the sense that they are willing to admit the faults of the heroes and heroines we once accepted uncritically. In the former telling of the fairytales we overlooked that at times they lied a little, stole some, ignored the oppressed, and were subtly greedy. However, where the films fail is in the moral direction they explore this idea. True to postmodern form, instead of heading in a subjective direction and exploring the heart of the hero a more objective path is taken. Postmoderns blame societies, never individuals and so heroes are what they are, not because of what they have done, but because of the advantage they are given. Our princes and princesses no longer triumph due to the power of absolute good; no, they triumphed because they had the greater advantage to manipulate the circumstances. They had more money, more resources, more favor, more looks. They were deeply flawed but ultimately they won because they were favored.

In the revisionist fairytales the villains are also re-cast in new light. The villains, once thought to be unquestionably and absolutely evil, suddenly become more like us. They are not as distantly dark as we once deemed them to be. Once the warlords of darkness, in the revisionist tales these sinister characters are merely underdogs who sold their souls for the sake of survival. Their hearts were broken. They were bullied and embittered. They didn’t turn their world dark out of malice, they did it out of defense against the cool kids.

Because postmodernism is essentially amoral, there is no longer a narrative of whether good can triumph over evil. The morality play has been assassinated in the postmodern era. These are no longer stories of morals, but of advantages. The princess with all the looks and a decided advantage created the witch. This is the postmodern fairytale.

The revisionist fairytale asks us not to condemn the villain but to sympathize with them. Villains are only the by-products of what it costs us to be prosperous. Things may appear to be snazzy in Camelot, but there is a darkness brewing somewhere that Camelot has created as a consequence.

Into the Woods promotes this idea brilliantly. As the giant approaches to crush our flawed cast of less than virtuous victors of situational ethics, they are left to introspectively mourn their mistakes in the woods. As each of them considers their own role in the making of the giant, an important question enters the equation - true to the form of the film - given to us in song - do we really have to kill it? After all, it is our fault that there is a giant coming to kill us.

This same tune is being sung in all of our media. The terrorist is not evil, he is an embittered victim of imperialism and capitalism. He would not even be here if it were not for the prosperity of our Camelot. Who’s to blame? And so our President apologizes to the world on our behalf. Dear dark world, please excuse the mess we have created. You hate us and its our fault. Every crisis from Isis to Al Queda, from a gunman in a theater to the looter in a riot in the streets - none of it evil, but each of them only a giant in a fit of rage that we have created in our prosperity.

In Into the Woods, the giant comes only because we interfered. Jack climbed the beanstalk and tampered with the giant’s world. And now, here she comes. If you haven’t seen the film, this may not make sense, but trust me when as I reiterate my synopsis - the film is your favorite fairy tale characters in a rugby scrum beneath the trees. Had Cinderella not wished to be a princess, had Jack not been forced to sell his favorite cow by his somewhat abusive mother, had the baker not been childless, had Red Riding Hood not been gluttonous, had the witch not been hoodwinked by the baker’s father, had his father not stolen the magic beans - there would have been no stalk that connected our world to that of the giants and we would have lived happily ever after - had we merely been content to leave well enough alone. Every choice made so that a wish may come true. Every wish that comes true does so at a cost to someone else.

What’s the answer? We have to kill the giant only because we were not brave enough to do what we should have done in the beginning - kill the wish!

If movies are culture sermons, the closing scene of Into the Woods was an indictment of our culture’s hopelessness. All we are left to do is retell the story - classic postmodernism. There is no real solution, only regret and confusion. Cinderella should have stayed a lowly abused house maid. Jack should have been content to be poor. The baker should have remained childless. Red Riding Hood should have stayed home.

The Bible was way ahead of film in teaching that prosperity should not come at the hands of oppressing others (Zech 7:10, Prov. 22:22-23, Jer. 7:5-7). There is a right way to rise. True, our wish should not be another’s nightmare. The film is right in this, greed and manipulation are false paths to prosperity. Yet the film fails to see that we need to instead be blessed by God as we walk in His ways. The key to the rise is to repent of evil, not to negotiate with it, apologize for it, or to socialize a society thinking somehow we will level the playing field and starve evil into extinction. The films portray our situation powerfully, but fail to solve it morally - evil is not the by-product of economics, but it is rather the by-product of a sinful soul. Thus, it is solved only one way, not economically, socially, or circumstantially - but through heart change.

The key to a more peaceful world is not more tolerance in the scrum beneath the trees, but repentance.

The Bible has a very clear view on evil that is in conflict with postmodern film. A person may be victimized, in a past life she may have been a good witch who had a tough go of it back in the day at Magic High with Glinda, but there is no valid excuse for evil. Instead of seeking to place responsibility on others and blaming them for the evil that is done, we are to look at ourselves and come to a place of honesty about what we have become.

The Bible finds only two solutions for evil. It must ether be crushed in righteous judgment or the evil one is offered a place of grace in repentance and faith. Evil does not go away if you apologize to it. Evil is not in the woods, it is in us. All of us are capable of foolish choices, ignoring the plight of the oppressed, and the pursuit of the ultimately selfish wish - we are capable, but we are also culpable for our actions.

Postmodernism and her films fail in thinking that people are never the problem, but rather the situation. In Into the Woods it is almost as if the whole thing is caused by the magic beans. It is not the existence of greedy or embittered people that brings evil into the world, but it is rather the existence of those cursed magic beans that promise prosperity. This is why postmodernism blames the gun instead of the gunman. People are not evil, situations are.

In its assassination of the morality play, postmodernism has become a naive fairytale indeed. Isis is not going to climb back up the vine just because I say “I’m sorry.” The school house gunman was not created by the gun manufacturer. Taking away his weapon will not change his heart. He does what he does not because of the cool kids. He does what he does because he is evil. In its refusal to call anyone evil or to celebrate anyone good, postmodernism rather teaches we are the product of Camelot. Yet the Bible teaches that we are not the products of our culture, our culture is the product of us.

In the end we are not left in the scrum beneath the trees to retell a pointless story and blame ourselves for what others do, but we are left with the gospel. The gospel is the story that Christ has entered our situation to change our hearts. The prince, the princess, the baker, the witch, the giant, all of us are confronted with a profound truth. The Son of God has come into the world to confront evil people in one of two ways: by grace or by judgment - we have a choice - either repent or perish. We cannot absolve ourselves in apologies for the existence of giants; pointlessly singing beneath the trees. We must face the truth. Evil is evil and it is in us. We do not need another false narrative to sing; we need to be redeemed.

Comments